History

EKA Timeline

EKA timeline100 Years of Art Education in Tallinn

by Mart Kalm

The First 20 Years: 1914 – 1934

The development of art education in the early 20th century Tallinn, which was the centre of Tsarist Russia’s Estonian province, is related to the recuperation of Estonian society and its rapid economic growth. For the Baltic-Germans, who were the old elite of the city, Tallinn (Reval in German) was so secondary in nature that the art school could peacefully exist in their spiritual capital – Riga. In 1891, when the university in Tartu discontinued its drawing classes, which did not prepare artists, but taught drawing as tool for scientific work, but still stimulated the local art scene, there was insufficient spiritual energy for founding an art school. As if sensing its own demise, the Baltic-German community focused its activities on the establishment of its own identity through the past. The Estonians were behind most of the new initiatives. They were the initiators and explorers who wanted to get ahead in every field of activity.

During the years preceding World War I, Tallinn experienced a genuine economic boom. The business revival caused by the preparation for the war saw several shipyards built in Kopli and the building of Peter the Great naval fortress was another huge enterprise, among many others. This growth resulted in rapid increases in the population of the city (1910 – 91,500; 1915 – 133,900). The new arrivals were comprised of the Estonians from the countryside as well as people from the other provinces. Almost all of them were employed as workers in the large factories, and the infrastructure of the city developed quickly. There was also room for plenty of small start-ups and artisans.

In Tallinn, the idea of founding an art school was promoted by the Estonian Art Society, which had been founded in 1907, and consolidated many of the more active members of Tallinn’s Estonian community under the leadership of the artists. It is noteworthy that the promotion of art was not left only to the artists, but it was seen as an important tool in nation building, and was supported by many successful Estonians. The idea of an art school was first realised in the form of the graphic art courses initiated in 1912, but it was hoped that they would quickly develop into an art school. At that time, the Estonian art community in Tallinn was dominated by art teachers who had studied at the Stieglitz Art School in St. Petersburg at the turn of the 20th century. Based on their educational background, they imagined an arts and crafts school that would educate skilled workers with a sense of design. Indeed, few art lovers participated in the art courses and the most popular were the technical drawing classes, because even basic drawing skills could ensure a good job in industry.

At the same time, in 1903, Ants Laikmaa, the most distinguished artist in Tallinn at the turn of the century, who had been educated in Dusseldorf, founded his atelier school and the highly acclaimed exhibitions that it organised significantly enlivened the art scene in Tallinn. When Laikmaa, who had the soul of an activist, was exiled in 1907, the school was closed, but when it reopened in 1913, a number of art-loving students that had participated in the graphic art courses went to study there (Oskar Kallis, Aleksander Krims, Alfred Tuul, and Aleksander Mülber). Perhaps, Laikmaa’s absence enabled the Stieglitz community to establish the type of school it wanted. Yet to hope that, had Laikmaa remained in Tallinn, his atelier school would have grown into a public art school is probably too much to expect. Despite Laikmaa’s charismatic personality, in economically booming Tallinn, there was a much greater demand for an arts-and-crafts-type school.

The opening of the Estonian Art Society’s Tallinn School of Arts and Crafts took place on 17 (30 based on the Gregorian calendar) October 1914. The Russian Ministry of Commerce and Industry had approved the school’s statutes in the summer, right before the outbreak of World War I. Establishing an art school on the Estonian educational landscape at the end of the Tsarist era was a significant step, because, except for the old University of Tartu (est. 1632), the other Estonian schools of higher education were not founded until immediately after World War I, at the beginning of the independence period. In 1918, courses were started at the Estonian Technical Society, which next year became the Tallinn College of Engineering. And the Higher Art School Pallas in Tartu and Higher Music Schools in Tallinn and Tartu were all established in 1919.

Right from the start, the Estonian Art Society’s Tallinn School of Arts and Crafts received substantial support from the city of Tallinn, and the school was transferred to the city in 1916. It became a state educational institution in 1920, although the word ‘Tallinn’ in its name was not deleted until 1924 when it became the State School of Arts and Crafts, which was the best known of the names of this institution of secondary vocational education.

Both the graphic art courses and school of arts and crafts operated at the Canute Guild Hall on Pikk Street in Tallinn. In the 1920s, the Tallinn College of Engineering was also located in the Canute Guild Hall, where architecture was also taught. In 2009, the EKA Department of Architecture and Urban Design moved there and initially so did the Department of Heritage Studies and Conservation, which meant that the architecture students had come full circle and returned to the space once occupied by their predecessors. When the Tsarist state ceased to exist, the State Secondary School for Girls was closed and the School of Arts and Crafts took possession of its two-story stone building on Tartu Road. The school remained in that building, which was repeatedly expanded, until 2010.

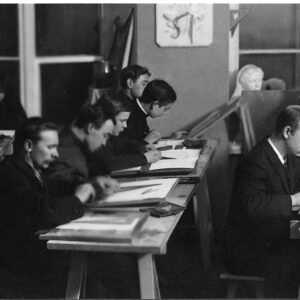

The instruction at the School of Arts and Crafts was originally in Russian, and was not switched to Estonian until independence was declared in 1918. Initially, students with a primary school education that were at least 12 years old were admitted. In 1918, the age limit was raised to 16. Essentially, during the independence period, the School of Arts and Crafts operated as a six-year vocational secondary school with an art focus, where general subjects and art-related subjects were both taught. In the 1920s, the students who had completed the three-year elementary program were qualified as skilled workers and after completing the advanced program were qualified in drawing and technical drawing. In the 1930s, studies started with a two-year general stage, followed by a three-year workshop stage and a one-year master class. Then, the school started admitting more secondary school graduates, who were sent directly to the workshops. The graduates were able to acquire further qualifications as drawing and handicrafts teachers by attending the Tallinn Teachers’ Seminar.

For the first 20 years, until 1934, the school was headed by Voldemar Päts, the politician Konstantin Päts’s brother, who had studied at the Stieglitz Art School in St. Petersburg at the turn of the century. He diligently implemented the drawing- and stylisation-based study methods he had learned there at the Tallinn School of Arts and Crafts. Päts himself graduated the Stieglitz School inconspicuously and did not become an artist, but he had sufficient pedagogical and bureaucratic talent. The nucleus of the faculty at the Tallinn School of Arts and Crafts consisted of Alfred Kivi, Osvald Jungberg (Noormägi), August Kilgas, Hans Kuusik, and Georg Rogožkin. All of them had studied drawing at the Stieglitz School, and were now drawing teachers. The internal opposition was formed by Roman Nyman and Nikolai Triik (until 1921), who had also studied at the Stieglitz School, but were renowned artists. However, famous artists continued to be rebuffed, and for instance, in 1926, attempts were made to get rid of Kristjan and Paul Raud. Jaan Koort, who had studied at the Stieglitz School, but was a troublemaker, did not fit in at all – not in the 1920s or in the 1930s. Technical drawing was taught by Herman Reier, who was an engineer and later the director of the Tallinn College of Engineering, and Teodor Ussisoo, one of the first Estonians to be educated as an interior architect, who later headed up the State School of Industry.

While the general art subjects at the arts and crafts school were taught in the turn-of-the-century spirit of national romanticism and Mir iskusstva, and art history did not cover anything beyond the Renaissance, the school’s strengths were in the workshops that taught practical skills. There, in addition to diligent and precise craftspeople, a whole series of genuine applied artists were educated. The school’s graduates not only helped to design products for successful businesses in the 1930s, like Taska, Lorup, Tavast and Kodukäsitöö, but a whole series of Soviet-era Estonian industries, like Juveel, Tarbeklaas, Linda, ARS, Kommunaar, Estoplast, the furniture factories, etc. relied on their knowhow and efficiency.

Along with the poster- and sign-painting workshop, another important workshop was the one for decorative painting, which was headed for a long time by stage designer Roman Nyman. Together with his students, Nyman designed the interiors for the restaurant in the prestigious Tallinn Social Club on Aia Street, etc. In 1925, classes in oil painting were added, which were taught by August Jansen who had been educated at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts.

The women’s handicraft department, which was originally called the needlework department (headed by Elfriede Paulberg, Helmi Koljo) and later called the embroidery speciality, was one of the most popular at the school. Since the school earned extra money by filling orders, the young women in this department were forever embroidering flags, Mari Adamson recalls.

In 1916, courses in bindery and working with cardboard were started for World War I invalids. A separate workshop developed from the leatherworking course, and next year, Voldemar Päts’s brother-in-law, Eduard Taska, was invited from St. Petersburg to head up the new workshop. Although printmaking techniques had been taught from the start, after an additional story was added to the schoolhouse in 1924, a proper workshop was equipped at the initiative of Günther Reindorff, and some of the equipment is still in use today. A separate printing school using the school’s infrastructure was also added.

During the independence period, the school’s graduates, who had supplemented their studies abroad, often took over the workshops and introduced new subjects. For example, when Eduard Taska, who had a keen business sense, founded his own private workshop in 1924, the school’s workshop was taken over by Adele Mels (Reindorff), who had graduated in 1921 and then continued her studies at the Hamburg School of Applied Arts in 1928 and, in 1938, at the Leipzig Higher School of Graphic Arts and Book Design. If Klara Zeidler, the Steiglitz graduate that headed the metal workshop between 1924 and 1934 cultivated filigree and enamel painting, then her successor, Otto Tammeraid, who graduated the school in 1926, and had continued his studies at art schools in Krefeld and Warmbrunn, started to forge candlesticks inspired by folk art and to produce tableware. The graduates who also introduced new fields of study included, for example, Linda Ormesson’s fashion design, Leonhard Pruuli’s building décor, and Paul Luhtein’s applied graphics.

In parallel with the professors from the Nordic countries, who developed the new national sciences at the University of Tartu in the 1920s, the teaching of ceramics at the School of Arts and Crafts was established by Professor Géza Jakó (1923–1933) from the Academy of Applied Art in Budapest. He was later replaced by Valli Talvik-Eller, who had graduated the school in Tallinn but continued her education in Helsinki and Faenza. If Jakó’s ceramics were opulently decorative in the national romanticist style, then Eller’s simple forms reflected a clear shift to modernism. Although the woodworking shop headed by Albert Hansen (graduated in 1924) remained anti-constructively decorative, in the 1930s, a renewal occurred in most of the specialities inspired by the art déco style. This is especially apparent in the glass cutting works of August Grünberg and Maks Roosma.

The most modern initiatives in the late 1930s were opening an interior architecture speciality under the direction of architect Konstantin Bölau and organising courses in garden and park design under the guidance of Arnold Alas (Hoffart), who had returned from Berlin.

If those interested in the fine arts usually went to the Pallas School in Tartu, and those who appreciated handicrafts to the Tallinn School of Arts and Crafts, many students started their education at the arts and crafts school and continued at the Pallas. For example, from 1915 to 1918, Eduard Wiiralt studied at the School of Arts and Crafts, but thereafter was in the first graduating class of the Pallas in 1924. Juhan Muks, Paul Liivak, Mari Adamson, Andrus Johani, Kaarel Liimand, Richard Sagrits, Salome Trei, Lepo Mikko, and others also continued their educations at the Pallas. However, there were also those who moved in the opposite direction: after a year at the Pallas, Valli Lember-Bogatkina came to the School of Arts and Crafts to study decorative painting, which she graduated in 1940.

Normal relations existed between the School of Arts and Crafts and the Pallas, which had been granted the status of a school of higher education in 1924, as long as the division of labour was clear, i.e. until the arts and crafts school limited itself to the teaching of applied arts and being a vocational school. The art public and critics had always admired the Pallas and paid much less attention, and rather more negative attention, to the old-fashioned school in Tallinn that was just drawing ornaments. However, when Voldemar Päts became the head of the Department of Vocational Education and deputy to the minister at the Ministry of Education he was able to enlist the support of the state to develop the arts and crafts school into a school of higher education and move into the field of fine arts. This was part of the centralisation policy of an authoritarian state, which was trying to neutralise liberal-minded Tartu. Inviting Professor Voldemar Mellik, who was teaching drawing at the Pallas, to come to Tallinn and head up the Department of Sculpture in 1935, and thereby escape the shadow of Anton Starkopf, who was head of the Pallas sculpture studio in Tartu, can be seen as a preparatory step in this direction.

The State School of Applied and Fine Arts: 1938

In 1938, a four-year State School of Applied and Fine Arts and a three-year State Higher School of Art were established on the foundation of the School of Arts and Crafts. Together they constituted the State Art Schools. The use of such a grand name was possible because the Pallas as a private school belonged to the art society. The State Higher School of Art included departments of painting, sculpture and applied arts. By the time the independence period ended, the quality of the Tallinn school had improved, and the graduates included several famous post-war artists. The first graduates of the State Higher Art School received their diplomas in 1941 and they included Evald Okas, Alo Hoidre, Oskar Raunam and others.

The War

In 1940, the Tallinn art schools were degradingly reunited into the State Applied Art School, which was named after Jaan Koort. Of course, during the first year of Soviet occupation, Koort’s name was appropriate, because he had gone to the Soviet Union in 1934, although only because he was not chosen to head the ceramics department instead of Jakó. Therefore, the selection of his name can be seen as revenge instigated by the June Communists with the support of the Pallas graduates. Initially, at Adamson-Eric’s recommendation, Ernst Kesa, a young art-loving architect was named to head the school. He did not represent any of the specialities taught at the school, but was supposed to see the integrated whole. Based on Bauhaus ideals, he established a structure that included departments of form, space, colour and books. After a few months, Anton Starkopf, who had been the director of the Pallas for a long time, was brought to Tallinn to head up the school. The power of those who had studied at the Stieglitz was broken and they were pensioned off or just fired. However, Johannes Greenberg, an authoritative Tallinn painter, and Erik Haamer from the Pallas were invited to come and teach at the school.

During the German occupation of 1942–1943, the school continued to operate under the name Tallinn School of Fine and Applied Arts. After the reopening of the Tartu school in 1943, the fine arts specialities were closed and the school operated as the Tallinn Applied Art School until the bombing of the city in March 1944. In late 1944, the school was reopened as a six-year school of higher education called the Tallinn State Applied Art Institute. The Institute had 12 departments including decorative-monumental painting, decorative-monumental sculpture, miniature painting, theatrical decoration, graphic arts, decorative leatherwork, textile and costume design, garden and park design, interior design, artistic ceramics and decorative glasswork. In 1946, the decorative metalwork speciality was reopened. Departments for teaching the school-wide subjects of Marxism-Leninism, composition, drawing and art history were also added.

In the second half of the 1940s, the school was headed by Adamson-Eric, who was a zealous critic of the pre-war School of Arts and Crafts, but who, in addition to his painting, had made a significant contribution to the applied arts. Most of the remaining faculty were old-timers (Karl Herman, Paul Luhtein, Adele Reindorff, Maks Roosma, Leo Soonpää, etc.), even Voldemar Mellik and Albert Hansen, who had headed up the school during the German occupation. New additions included architects Edgar Kuusik and Edgar Velbri, textile designer Mari Adamson, costume designer Natalie Mei, etc. Adamson-Eric was able to have a disproportionately large number of faculty members successfully qualified as associate professors and professors, supposedly by using his contacts in Moscow.

The ERKI Years

However, in the late 1940s, when Moscow’s lenient attitude toward the annexed Baltic countries changed, it was discovered that the Applied Art Institute was a den of bourgeois nationalism. In 1949, Adamson-Eric was replaced as director by Friedrich Leht, an Estonian who came from Russia. As a graduate of the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, he sincerely believed in realism and eagerly tried to introduce it. As someone that came from the outside, he was also the right person to resolve the hostilities that had existed between the art schools in Tallinn and Tartu for over 20 years. If at first, the plan was to divide the duplicated specialities between the two schools, then at the end of 1950, Moscow decided to merge the Tartu State Art Institute with the Tallinn State Applied Art Institute, and thereby establish the State Art Institute of the Estonian SSR (ERKI, an acronym based on the Estonian-language name). This blow to Tartu as the city of art was part of the campaign to destroy Tartu as the centre of national intellectual life. The students who had been admitted to the school in Tartu were allowed to complete their courses in the ERKI’s Tartu branch until 1955. The Tartu Art School, which provided a secondary education, was established, which according to the concept of the day, was supposed to teach the skills necessary for being admitted to the ERKI. Today, this school has developed into the Tartu Art College.

The architecture speciality was opened in the updated art school. The Tallinn Polytechnic Institute (TPI), which had admitted a large number of architectural students right after the war, had discontinued the admissions, therefore forcing the architectural circles to find a new home for the speciality. The Stalinist approach to architecture was well suited to architectural studies in an art school (read: art academy), because the architecture taught at an engineering school was not as aesthetic. However, the price of opening the architecture speciality was the closing of the garden and park design and interior design specialities. Oleg Ljalin was brought from Leningrad to head up the Department of Architecture. Edgar Kuusik, who had been thrown out of the Union of Architects, was probably too sinful to become the head of the new department, which is why a dark horse had to be brought from Russia. At the same time, Leht, who did not know the local artists, tried to make due with the existing forces despite the pressure for a purge.

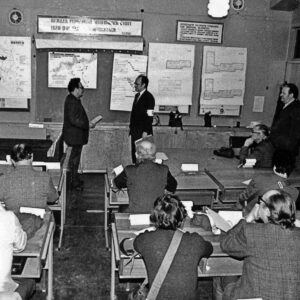

The work done by the students in the early 1950s is representative of the most fearfully orthodox Stalinism. Leht introduced parallel Russian-language classes, which opened the school to students from Russia. In order for the Estonians to compete with those who had been trained at the secondary art schools in Russia, preparatory courses were added in 1952. Summer training programmes, which were not part of the pre-war studies, were introduced during the Soviet period. They were conducted at the school’s summer cottages in Vääna-Jõesuu, as well as elsewhere in Estonia. An evening division was opened for architectural studies.

The second half of the 1950s brought some modest liberalisation to the ERKI. The young sculptor Jaan Vares, who became rector in 1959, was certainly a refreshing change to the unilingual Stalinist Leht. Vares, who remained in his job for 30 years, was a skilful tightrope walker, who knew how to maintain relations with his superiors and allow quite a lot of freedom within the school. At his initiative, the school building was expanded in two stages and new specialities developed. For example, alongside the restored interior architecture department, in 1966 Bruno Tomberg established the design department. Starting in 1963, an extensive student exchange programme was instituted with art schools in the socialist countries (Leipzig, Halle, Budapest, Bratislava, Krakow, etc.). Finnish schools, with whom joint competitions were even organised, withdrew their cooperation after Soviet tanks rolled into Prague in 1968. In the course of Union-wide cooperation, the ERKI started to educate applied artists and interior architects for Latvia and Lithuania, later also for Moldava and Mongolia. Individual students were sent to further their studies in the stronger specialities of schools of higher education in the Eastern Bloc (book design, photography, design, landscape architecture, and glass).

The convergence of all higher fine art education in Tallinn posed a great challenge for a school that had only taught applied arts until that time. And this was difficult to cope with. Sometimes the fine artists were disturbed by the fact that they were attending a school of applied arts, and the applied artists were disturbed by the fact that they were considered second-rate compared to the fine artists. If the Stalinist era still favoured perfect execution in the tradition of an arts and crafts school, then starting with the Thaw, the balance shifted to bohemian liberalism that valued the creativity of the fine artists. The faculty included Pallas graduates, like sculptors Martin Saks and Enn Roos, painters Lepo Mikko, Valerian Loik, and starting in 1957, Johannes Võerahansu, but there were also numerous faculty members who had graduated from the School of Arts and Crafts, like Paul Luhtein, Aleksander Kaasik, Oskar Raunam, Evald Okas, Alo Hoidre, and Arnold Alas. A large number of the faculty members were united by the time they spent in Yaroslavl during the war. This had not provided opportunities for their creative development, but being on the ‘right side’ in the war ensured symbolic capital in the Soviet society that helped them maintain their positions as faculty members, who were well paid at the time. The Department of Painting was headed until 1983 by Ilmar Kimm, an Estonian from Russia, who was not well known as a painter. It is no wonder that already in the 1960s, the faculty members no longer served as authorities for the students and the path that Estonian art was following differed significantly from what was being taught at the ERKI. ANK’64 and SOUP’69 were two significant groups that developed among the innovatively minded students. The charismatic Tõnis Vint functioned as a guru that provided an alternative to the school up until the 1980s. In school, no change was apparent until the 1980s, when Enn Põldroos, Tiit Pääasuke and Ando Keskküla arrived in the painting department, Vive Tolli and Enno Ootsing in the graphic arts department, and Jaak Soans in the sculpture department.

Things were more positive for the applied arts specialities. The art innovations of the late 1950s and early 1960s, established a firmer footing here than in the fine arts departments. The applied artists with a school of arts and crafts background were generally stronger in their areas of speciality than the fine artists. And the transition from the generation that matured before the war (Adele Reindorff, Mari Adamson, Leesi Erm, Ede Kurrel, Arseni Mölder, and Maks Roosma) to the post-war generation (Ella Külv, Ella Summatavet, Salme Raunam, Leili Kuldkepp, Leo Rohlin, and Maie-Ann Raun) was smoother.

The architecture and interior architecture departments were filled from the very beginning with the respected pre-war architects Edgar Kuusik, Edgar Velbri, Peeter Tarvas, August Volberg and Alar Kotli. Oleg Ljalin sensed his role and returned to Leningrad after losing the support of the Communist Party. The generation of architects who graduated from the Tallinn Polytechnic Institute and became faculty members at the ERKI included Mart Port, Voldemar Herkel, Heino Parmas and Helmut Oruvee, who was invited from the TPI because of his doctoral degree in acoustics. A very sharp conflict flared up in the Department of Architecture during the 1970s between the modernist faculty members, who had adapted to the situation, and the angry young postmodernist generation. In comparison with the admirable interwar-period work of the older faculty members, the Soviet mass construction seemed especially feeble. During the Soviet era, engineering faculty members like Dmitri Tenisberg, Ilmar Kiiss and others also taught at the ERKI; and architectural history was transferred from Ernst Ederberg, who had studied in Riga, to Rein Zobel, who had graduated from the Tallinn Polytechnic Institute. The Department of Interior Architecture was headed by Väino Tamm, who had the unusual experience of interning in Finland from 1967 to 1968, and who, together with Vello Asi and Leila Pärtelpoeg, was able to inspire the young people.

The former radical Kaljo Põllu, in whom an interest in Finno-Ugric mythology had burgeoned, arrived in the Department of Drawing in 1975 from the Art Cabinet at the Tartu State University. In 1978, he started to organise school-wide student expeditions to visit kindred Finno-Ugric peoples, which continue today. Introducing art students who hungered for the West to kindred peoples that cultivated traditional culture constructed a new identity and was artistically inflaming.

On the Estonian higher education landscape of the 1970s and 1980s, the ERKI had quite an elitist reputation, because it was very hard to get into the school, but certain bohemian freedoms were accepted there. The ERKI students, with their home-sewn clothes, stood out in the grey Soviet street scene. The ERKI fashion shows (starting in 1982), which were a playful self-initiative, tried to introduce a more liberal style of clothing and as an after-effect, fashion shows are still being organised in secondary schools today. The ERKI parties were renowned, and were a springboard for musical groups like Peoleo, Turist, Päratrust, and Singer Vinger.

The Singing Revolution and the Spirit of Freedom

Since the school felt guilty about the liquidation of the legendary higher art education in Tartu, in 1989, propelled by the romantic winds of the Singing Revolution, a branch of the Department of Painting was established in Tartu with the collaboration of the University of Tartu. The local art scene was given a strong impulse by this and the department is still operating as the Chair of Painting at the University of Tartu under the direction of Jaan Elken.

Already before the restoration of the Republic of Estonia, the school was renamed the Tallinn Art University at the initiative of Rector Jaak Kangilaski. During the tenure of the next rector, Ando Keskküla, the name, which had already been embraced, was changed to the Estonian Academy of Arts, based on the example of the Estonian Academy of Music, in the hope that the higher schools of art would be given equal treatment by the state.

The transition period brought about a generational change. The new social changes were too radical to be carried out by those who had served the Soviet authorities their entire lives, no matter whether they had done so willingly or unwillingly. However, to a certain extent, the new forces that had arrived in the 1990s now started to be replaced by the next generation.

Thus, just like the Soviet regime had reorganised the School of Arts and Crafts to suit itself, now one had to get used to reforms, and concepts like public university, state-financed students, subject credits, BA, MA and PhD studies, and professors emeritus. The visiting lecturers and non-Estonian students spoke English instead of Russian; Moscow’s controls were replaced by international certifiers; Proceedings started to be published and a publishing house was established; along with lectures, real seminars were introduced; and art students started to participate and join in the discussions when their work was being assessed, which had been done behind closed doors during the Soviet era. When, in the mid-1990s, the number of classes at the school were counted, and brought into conformity with the standard workloads for faculty members, several educators lost their jobs. The excellent salaries of the Soviet-era professors dried up, and a warning strike was even planned. In 1990, there was no money to renovate the Estonian-era Tamse schoolhouse in Muhu as a training centre. The Vääna training centre had to be abandoned due to the land reform, and the Türisalu centre that was acquired in 1997 was never started up. By 2000, the Soviet-era gymnasium had been rebuilt into a modern library, which reflected the altered nature of art studies. The school’s foyer, where exhibitions had been always organised, was institutionalised in 1996 into the EKA Gallery. Starting in 1999, the annual exhibitions of the students’ graduation projects have been organised outside the school, mostly at the Rotermann Salt Storage and since 2007 under the name of TASE.

At the initiative of Rector Jaak Kangilaski, art history was introduced as a speciality in 1992. The art public was not satisfied with the narrow historical orientation of the art history studies at the University of Tartu, and there were qualified faculty members at the Art University already teaching art history and aesthetics to artists, who were also capable of educating art historians. Since the late 1990s, the school’s only research topic that receives targeted financing from the state has been accommodated at the Institute of Art History (KTI). Since 1998, a project to write a new history of Estonian art (general editor Krista Kodres) has been underway under the direction of the KTI and three volumes have been published to date. At the initiative of Juhan Maiste, during the final years of the 20th century, the conservation speciality separated from the Institute of Art History and now it is the Department of Heritage Studies and Conservation. The building on Suur-Kloostri Street that now houses the entire Faculty of Art and Culture was reconstructed in 2007.

Rector Keskküla was truly captivated by the new technological possibilities of the world that had opened up. In 1994, an e-media centre was created, which grew into the Chair of New Media, which was established in 2000. In the mid-1990s, Peeter Linnap, who headed the Photography Centre, caused an upheaval in Estonian art, and in 2001, photography, which had been excluded from the art field for a long time, was established as a speciality. In 2001, a department for interdisciplinary arts was also founded; this later became performance arts. The newer MA curricula, which are taught in English, include urban studies (2004) and animation (2007), as well as the design and product development curriculum run jointly with the Tallinn University of Technology (2011). The current faculty structure (fine arts, design, architecture, and art and culture) resulted from the reorganisation in 2006.

The Open Academy, which offers learning opportunities to working adults, was established in 1997. In-service training for art teachers and conservators was started even earlier. In the wave of higher education expansion at the turn of the millennium, the EKA experimented with a Russian-language Applied Art College (1998–2005) and the Academia Grata in Pärnu (2002–2004).

A great change for the art school was the introduction of doctoral studies in 1995. Initially, mainly well-known scholars defended their doctoral theses as external students, because they wished to acquire ‘real’ PhD degrees in addition to their Soviet-era candidate degrees. The art history curriculum, introduced first, represented the traditional humanities; while the programmes of heritage studies and conservation, art and design, as well as architecture, are based on creative practices.

When Signe Kivi, a textile artist and politician, became rector in 2005, the issue of a new building started to be seriously dealt with. In 2008, an international architectural competition was organised, and first place went to the 16-story Art Plaza tower designed by a group of young Danish architects. Having faith in the Government of the Republic, which had allocated resources from EU Structural Funds for the construction of the new building, the EKA demolished its old building in 2010 in order to accelerate the process. Unfortunately, this was followed by misgivings regarding the necessity of the building and the suitability of the project; the minister of education even questioned the sustainability of the school, and the EKA, which had been spread out in leased spaces, had to find new alternatives. The administration, library and Faculty of Design re-situated to 7 Estonia Boulevard, the Faculty of Fine Arts to the former Building of Estonian Knighthood (Rüütelkonna hoone) on Toompea Hill and its Sculpture Department in the former ARS monumental art building on Raja Street. The architecture department relocated to the Canute Guild Hall on Pikk Street, while the Faculty of Art Culture operated on Suur-Kloostri Street. However, in order to get a new building, the EKA, unlike the other public universities, had to sell all its former assets.

In 2013, the school acquired the former Rauaniidi factory building on the corner of Põhja Boulevard and Kotzebue Street, which was under heritage protection. In the summer of 2014, a competition was organised for adapting the industrial complex to the needs of the school, which was won by Kuu Architects for its conceptual solution called Linea (authors: architects Joel Kopli, Koit Ojaliiv and Juhan Rohtla, and philosopher Eik Hermann). EKA moved into its new premises in the summer of 2018.

The Academy of Arts has never faced challenges as serious as today’s. The mission of the school is to defend visual culture in Estonia. Maybe the public battle against the artistically inferior Freedom Monument, the so-called ‘monument war’ of 2009, cost the school its new building, but there can be no compromise in the defence of these values. This is Academy of Arts’ qualified contribution to a knowledge-based Estonia. The neoliberal social order had marginalised not only art, but also architecture and design, not to mention eradicating art criticism. The creative economy has potential, but a mere business model cannot replace fundamental disciplines. The competition between the schools of higher education in Estonia and abroad has intensified. The attitude toward life of the dwindling number of young people is increasingly rational. Yet, an oasis for the idealistic remaking of the world must exist somewhere. In its new century, it will be exciting for the EKA to meet these and other, yet to arise, challenges.