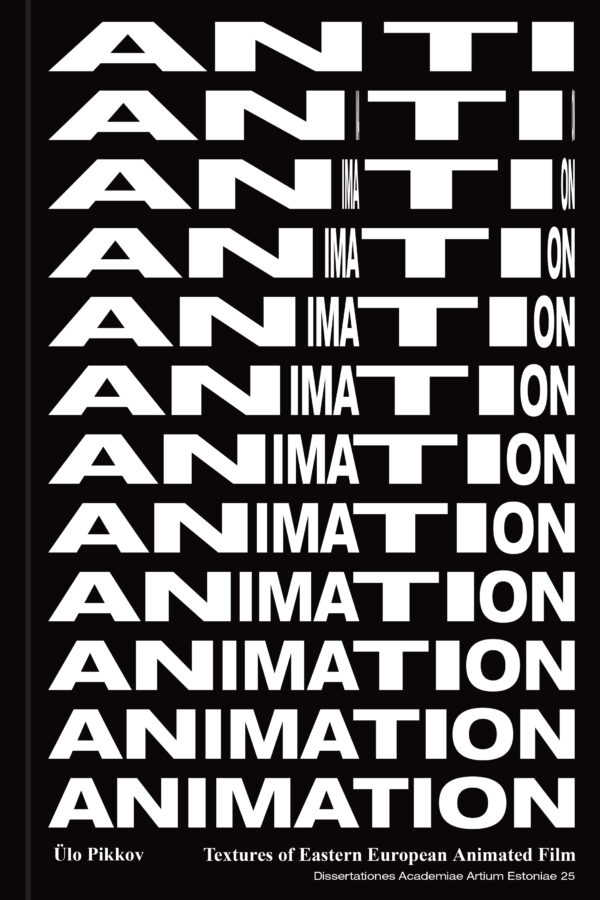

Even though the origins and early formation of animated film in Eastern and Western Europe shared certain similarities and common ground, the face of the post-World War II animated film in Eastern Europe was shaped by planned economy, centralised industrial structure, political censorship and a number of other factors that stood in stark contrast to the principles of free market economy. Hence, in my view, Eastern European animated film of the Soviet period can be defined as anti-animation, that is, animated films produced under political pressure and in contradiction to capitalist industrial logic.

Anti-animation – animated films produced under the conditions of a totalitarian regime that, contrary to those made in the ‘free world’, were shaped by socialist command economy and political censorship.

The tradition of animated film that emerged in Eastern Europe after the end of World War II was completely unique in terms of enjoying access to ample, state-assigned resources of production, while being subjugated to constant political surveillance. At times, ‘parallel universes’ appeared to exist in studios – directors were relatively unconstrained in their artistic pursuits, while script editors assigned to them had to take care that only the politically ‘correct’ results of their work would reach the audiences. The animated film of a totalitarian society reflects the pressures of totalitarianism.

In order to overcome these constraints, Eastern European animation artists often relied on metaphors, employing the so-called Aesopian language that provided means for criticising the authorities indirectly, via metaphorical elements. Lev Loseff, a renown scholar of Aesopian language, emphasises that the use (i.e. decoding) of Aesopian language requires the efforts of not only a reader, but also those of an author and a censor. Decoding, searching for and producing of all kinds of interpretations and connections played a crucial role in Soviet animated film, as well as in Soviet culture in general.

Indeed, animated film was the ‘channel’ that introduced several manifestations of Western pop culture to Soviet audiences.

The unique cultural milieu and complex history of Eastern Europe has shaped an unparalleled tradition of animated film, the study of which will offer us a better understanding of the region’s past and its people.

Animated film continues to serve as a vehicle of cultural memory, national mentality and identity. Animated film provides useful insights into broader social processes.

Supervisor: dr Raivo Kelomees (Estonian Academy of Arts)

External Reviewers: prof dr Robert Sowa (Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow) and dr Michal Bobrowski (Jagiellonian University)

Opponent: prof dr Robert Sowa (Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow)

Copy editor (English): Eva Näripea, Richard Adang

English translation: Eva Näripea

Graphic design: Margus Tamm

Dissertationes Academiae Artium Estoniae 25

264 lk, in English

Estonian Academy of Arts, 2018

ISBN 978-9949-594-61-0 (print)

ISBN 978-9949-594-62-7 (pdf)

ISSN 1736-2261