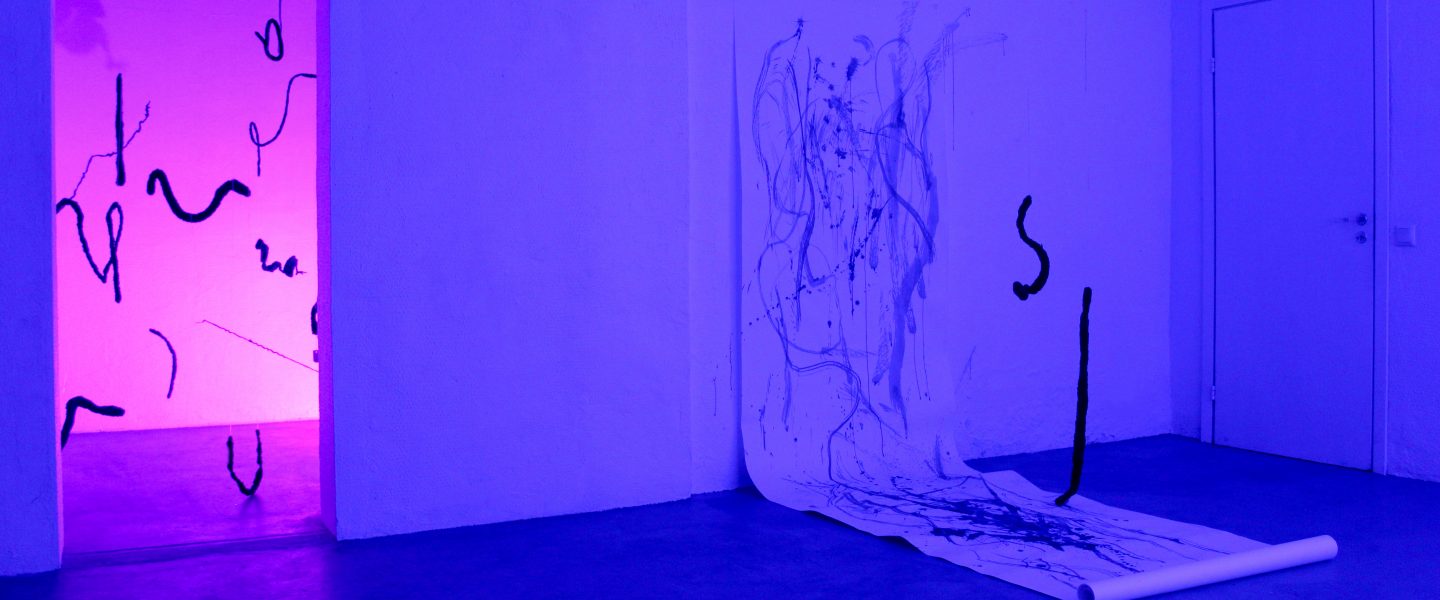

"I drew a line", Vent Space residentuuriprogrammis osaleva kunstniku töö.

Inês Rodrigues Neves on eeskätt tegija. Hetkel õpib ta EKAs Tekstiilidisaini õppekaval. Neves kasutab kogemusi, vaatenurki ja suhteid kui materjali, mida avastab läbi ruumisuhete. Olgu nendeks interjöör ja eksterjöör, mina ja teised, nähtav ja nähtamatu. Oma Vent Space residentuuriprogrammis arendas noor Portugalist pärit kunstnik oma magistritööd. Vent Space meeskond pani temaga koos töötama Matej Chrenka, kes töötas Vent Space kirjasõna residentuuriprogrammis.

Matej Chrenka on slovakk, kes õpib hetkel Tomas Bata Ülikooli doktorantuuris. Varasemalt on kunstnik õppinud fotograafiat.

Chrenka jagab oma mõtteid joontest, joonestamisest, joondumisest, millega ka Neves projektiruumis nädalapikkuses residentuuriprogrammis tegelemas oli:

It is almost inconceivable to create any sort of visual composition without firstly outlining basic shapes. No matter what technique is used, it usually starts with a simple sketch of basic lines that artist use to gradually build the final picture. No matter how basic part they may seem to play, number of various meaning they can convey is potentially infinite.

Reading the lines

The most fundamental function of the lines is related to a text as a means of communication. Either in a form of an alphabet, symbols or pictures, its role is to convey a coherent piece of information connecting one idea with another. Not only it is able to store a content, but its innate capability is also to give the message a linear and causal structure. This mode of interaction creates a deeply rooted cultural bias of this simple visual element and evokes an inherent sense of continuity that we usually associate with it. Therefore, it comes naturally to approach the line from the perspective of reading.

You read these lines word by word or even a sentence by sentence and you assume that you are in command. However, your eyes are following the course of these lines. You maybe skip a word from time to time. But your eyes probably move through the page in a very predictable fashion dictated by the layout of the text. We can consider the act of reading as an expression of a voluntary consent to surrender. The only way how to make the act of reading sensible and give meaning to the activity is to surrender to the dictate of the lines.

Lines themselves in this context serve as a carrier of information that needs to be extracted and recomposed in the reader’s mind. They tend to blend into a unified mixture of symbols and in this process the aesthetic qualities seem to be rendered irrelevant or almost invisible. It is a prerogative of art to bring our attention to the expressive nature of a line but not exclusively.

Think of a signature.

A unique composition of stylized lines or even a single line can represent the authenticity of an individual. By signing we authorize documents, prove our physical presence, give consent or validate information. The concept of authenticity expressed through a unique trace of hand movement is deeply rooted. When we look at the general practice of collecting autographs for instance, we can assume that such a simple act of signing implicitly represents the ephemeral individuality of the person. It instantaneously evokes a sense of intimate presence.

Similarly, a love letter composed in a text editing software with a perfectly homogenous layout and standardized digital typeset sent via email however sincere and affectionate will never be able to replace the hand-written piece. Using the perspective of Walter Benjamin, the aura of the old-fashioned letter provides us with a sense of mediated physical connection. Our hands are touching the very same object that somebody else held. Such a letter would contain many other details that are any less meaningful. The qualities of the lines could tell the story of their own. Interruptions in the flow of the text, a sign of mental inhibition preventing the writer from expressing something false or problematic. Sudden rush of intense emotions when the hand lagging behind the words being articulated in mind moves on the paper almost autonomously creating an unruly passionate line. Every misprint, solecism otherwise autocorrected in the digital era, or even a drops and smudges on the paper could convey a meaning. But not only these tangible details create the special experience. As Benjamin mentions there is also one more layer, the whole history of love letters written by hand that connect us to the full archive of romantic tradition.

Line as an object.

One of the greatest achievements of renaissance painting undoubtedly remains the discovery of rules of perspective. This very moment in history marks an unprecedented breaking point in our perception of visual art that enables us to perceive otherwise flat surface of canvas as a representation of an imaginary space. By following complex yet easy to intuitively understand principles of geometry we can adjust the arrangement of lines to create a convincing illusion.

What ultimately creates a sense of depth is a shadow. Not only it creates a relation between the depicted object and their surroundings it also gives us an information about the space reaching far behind the realm on canvas. The distance of the light source from the scene, its intensity even traces of obstacles standing in a way of light could be intuitively guessed based on the shadow. Interestingly, following painterly logic, lines composing any traditional art piece cannot cast a shadow. In this case lines could be understood as metaphorical membranes between imaginary and real. From the ‘’perspective’’ of painting lines simply does not exist no matter how dominant part of the picture they create, and they are not perceived as individual real entities. Imagine having absolute vision with infinite capacity to perceive details. With no limits to distinguish between visual discrepancies lines would simply cease to exist. Therefore, line is nothing else than the minds’ best attempt to simplify, to omit infinite number of details creating the world. It represents limitations of our senses in a beautifully lazy and reductive manner.

Can we experience a line and how?

Lines are usually perceived as inanimate objects. It is the responsibility of the reader who by focused attention can bring them to life. The everyday interaction with lines is principally in a mode of solitary contemplation which prevents us from a shared experience because we are culturally biased to interact with lines in the solitude of our mind. We have been taught to read sitting still in quiet after all. Can we question and challenge this habit?

The line itself provokes an action. Subtle impulse triggers movement in our eyes that almost involuntarily start following the direction of the composition. In order to see different angles and perspectives we need to navigate our bodies through the space. Our experience of the composition is taking place ‘’outside’’ rather than virtual realm of ones’ mind. An interesting by-product of this interaction such as humble act of stepping aside bowing or squatting sends an observable physical signal to our environment upon which a further connection can be established. By consciously engaging the human body in the process of reading, we open ourselves for a new level of perception and interaction with others. Just imagine people moving around the line/object as dancers collectively creating an improvised and ever-changing choreography when the piece itself becomes a score.

Line as motion.

Every line implies a preceding hand or body movement. In the tradition of academic painting, a way these movements were conducted suggested a highly skilled craftsman in total command of his tools. Absolute obedience of the resulting line was the ideal. Not until the mid-nineteenth century a notion of an unruly, extravagant or emotional quality of line would be taken into serious consideration. And it took almost one additional century to come to a fully confident expressionist lines in works of artist such as Jackson Pollock that established a gestural painting as legitimate movement or method of work.

Expressing the line in space rather than on a plane opens a new perspective to the tradition of this style. But interestingly, it serves purpose of both a transcript of the author’s movement and an instruction for the reader’s spatial navigation. Walking in between suspended lines creates an extraordinary feeling of walking through the inside of a book paradoxically consisting of a sign language. Almost as if the actual subject of the piece is immanent presence of the artist herself and whole spectrum of indexical reading unfolds. Each object represents a maneuver or an action leaving an imprint in the gallery space.

Lines seem to be an obscure phenomenon. They provide visual compositions with structural support and coherence, but only rarely they seem to be an independent subject on their own. Despite their crucial role in any art form, their status remains very humble and only inspected with keen eye, they can unveil a whole universe of expressions.

1.

In even the most perfect reproduction, one thing is lacking: the here and now of

the work of art—its unique existence at the place at which it is to be found. The

history to which the work of art has been subjected as it persists over time

occurs in regard to this unique existence—and to nothing else.

Benjamin, Walter, et al. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. 1st ed., Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008, p. 13.

2. Considering that women were prevalently denied access to academic training the misuse of gender biased language appears to be legitimate.